If we are going to bend the emissions curve, then a majority of businesses need to get involved and emissions accounting must become as commonplace as financial accounting.

By Kumar Venkat and Susan Cholette

Imagine a world where many businesses — large and small — quantify their greenhouse gas emissions annually and develop plans for cutting emissions. Imagine also that emissions accounting and planning are no more complicated or expensive than financial accounting and planning.

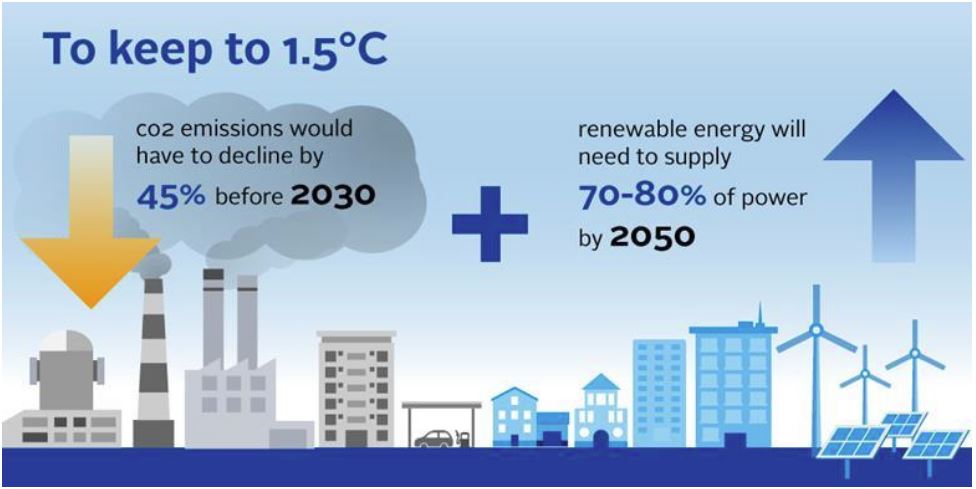

This imaginary world is not just nice to have, but will be essential if we are going to have any chance of holding the warming to 1.5 degrees or even 2 degrees. The window for 1.5 degrees pretty much closes in 2030. By that year we will need to have cut emissions 45% from 2010 levels to have a shot at 1.5 degrees, or 20% for a more devastating 2 degree temperature rise.

To achieve emission reductions of these magnitudes, we will need to turn the first half of this coming decade into a transition period where we begin bending the emissions curve even as we wait for coherent national and international climate strategies. Businesses can switch to clean energy, improve energy efficiency, move to materials with lower life-cycle emissions, adopt or even invest in carbon capture technologies, and as a last resort find high-quality carbon offsets to neutralize the remaining emissions in their operations.

If these voluntary actions actually take place at a sufficient scale in the next several years, they will have an outsized impact on our future temperature trajectory. But we can’t cut emissions without knowing where we stand. Before businesses can take action, they will need to quantify their emissions at least annually similar to an annual financial review. Ideally, a review like this will show not just a year-to-year trend but also real opportunities for emissions reduction. There have been two long-standing obstacles to doing this on a large scale across the economy.

The first and biggest obstacle is cost. A typical corporate greenhouse gas inventory or a product carbon footprint can cost anywhere from a few thousand dollars to tens of thousands of dollars. For companies with many different products and complex operations, the cost can quickly become prohibitive. Not many companies have the budget to undertake a one-time footprinting exercise, let alone do it on an annual basis. Given the millions of businesses and the tens of millions of products in the US alone, there isn’t enough money in the world to footprint everything at these price points.

The second obstacle is time. We only have this coming decade to turn the emissions trajectory around and begin an era of annually decreasing emissions. Conventional carbon footprinting exercises can take anywhere from a few weeks to many months. We just don’t have the time (or the army of consultants) to footprint everything at this pace.

It is not enough for just the largest or the most socially responsible companies to quantify their emissions. If we are going to bend the emissions curve, then a majority of businesses need to get involved, and emissions accounting must become as commonplace as financial accounting. This can only be achieved with highly streamlined and standardized life-cycle assessments and greenhouse gas inventories that can be performed on a mass scale at a small fraction of the cost and time they have required in the past.

We have a few suggestions on how to get there. The first and most important step is automation. We should leverage modern cloud computing and databases to compute, store and report results rapidly. Spreadsheet-based analysis should become a thing of the past.

Once we have an automated framework for carbon modeling, we should decide on the level of accuracy needed. For the vast majority of business applications, secondary life-cycle inventory data for upstream purchases and downstream activities should provide more than enough accuracy for identifying the significant emission sources and considering options to reduce those emissions. Moreover, this can be supplemented with economic input-output data in order to limit any inaccuracy that may occur due to cutoffs. This type of simplification is common in many engineering disciplines and is essential for high-volume carbon modeling.

Accounting standards already exist for corporate and product carbon footprints, but allow a fair amount of leeway in how specific scenarios are modeled. In the interests of saving time and effort, we should adopt a standardized methodology for modeling common issues that many businesses will encounter (such as recycling and waste disposal) as well as less common ones (such as time-dependent storage and release of carbon in soils, vegetation, and built structures).

With automation, simplification, and standardization, we have a real opportunity to make emissions accounting accessible to businesses of all sizes. If done right, this could be step one in the fight to hold the line at 1.5 degrees.

— —

Kumar Venkat is president of CleanMetrics 2.0. Susan Cholette is vice president of consulting services at CleanMetrics 2.0 and a professor of decision sciences at San Francisco State University.